Author unknown; written in Northeast Midlands English around 1285 AD.

Translated by Ken Eckert

Middle English text from Herzman, Drake & Salisbury’s Four Romances of England (1999), Kalamazoo, MI

For educational use only.

Havelok Stone, Grimsby Havelok Stone, Grimsby |

Hear a sample of Havelok, lines 1-16. I could not find an existing recording and so this is my voice doing my best to reproduce the sound of English circa 1285. |

|

| 1 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150 160 170 180 190 200 210 220 230 240 250 260 270 280 290 300 310 320 330 340 350 360 370 380 390 400 410 420 430 440 450 460 470 480 490 500 510 520 530 540 550 560 570 580 590 600 610 620 630 640 650 660 670 680 690 700 710 720 730 740 750 760 770 780 790 800 810 820 830 840 850 860 870 880 890 900 910 920 930 940 950 960 970 980 990 |

Herkneth to me, gode men - Wives, maydnes, and alle men - Of a tale that ich you wile telle, Wo so it wile here and therto dwelle. The tale is of Havelok imaked: Whil he was litel, he yede ful naked. Havelok was a ful god gome - He was ful god in everi trome; He was the wicteste man at nede That thurte riden on ani stede. That ye mowen now yhere, And the tale you mowen ylere, At the biginnig of ure tale, Fil me a cuppe of ful god ale; And wile drinken, her I spelle, That Crist us shilde alle fro helle. Krist late us hevere so for to do That we moten comen Him to; And, witthat it mote ben so, Benedicamus Domino! Here I schal biginnen a rym; Krist us yeve wel god fyn! The rym is maked of Havelok - A stalworthi man in a flok. He was the stalwortheste man at nede That may riden on ani stede. It was a king bi are dawes, That in his time were gode lawes He dede maken and ful wel holden; Hym lovede yung, him lovede holde - Erl and barun, dreng and thayn, Knict, bondeman, and swain, Wydues, maydnes, prestes and clerkes, And al for hise gode werkes. He lovede God with al his micth, And Holy Kirke, and soth ant ricth. Ricthwise men he lovede alle, And overal made hem for to calle. Wreieres and wrobberes made he falle And hated hem so man doth galle; Utlawes and theves made he bynde, Alle that he micte fynde, And heye hengen on galwe-tre - For hem ne yede gold ne fee! In that time a man that bore Wel fifty pund, I wot, or more, Of red gold upon hiis bac, In a male with or blac, Ne funde he non that him misseyde, Ne with ivele on hond leyde. Thanne micthe chapmen fare Thuruth Englond wit here ware, And baldelike beye and sellen, Overal ther he wilen dwellen - In gode burwes and therfram Ne funden he non that dede hem sham, That he ne weren sone to sorwe brouth, And pouere maked and browt to nouth. Thanne was Engelond at hayse - Michel was swich a king to preyse That held so Englond in grith! Krist of hevene was him with - He was Engelondes blome. Was non so bold louerd to Rome That durste upon his bringhe Hunger ne here - wicke thinghe. Hwan he fellede hise foos, He made hem lurken and crepen in wros - The hidden hem alle and helden hem stille, And diden al his herte wille. Ricth he lovede of alle thinge - To wronge micht him noman bringe, Ne for silver ne for gold, So was he his soule hold. To the faderles was he rath - Wo so dede hem wrong or lath, Were it clerc or were it knicth, He dede hem sone to haven ricth; And wo dide widuen wrong, Were he nevre knicth so strong, That he ne made him sone kesten In feteres and ful faste festen; And wo so dide maydne shame Of hire bodi or brouth in blame, Bute it were bi hire wille, He made him sone of limes spille. He was the beste knith at nede That hevere micthe riden on stede, Or wepne wagge or folc ut lede; Of knith ne havede he nevere drede, That he ne sprong forth so sparke of glede, And lete him knawe of hise hand dede, Hu he couthe with wepne spede; And other he refte him hors or wede, Or made him sone handes sprede And “Louerd, merci!” loude grede. He was large and no wicth gnede. Havede he non so god brede Ne on his bord non so god shrede, That he ne wolde thorwit fede Poure that on fote yede, Forto haven of Him the mede That for us wolde on Rode blede - Crist, that al kan wisse and rede That evere woneth in any thede. The king was hoten Athelwold. Of word, of wepne, he was bold. In Engeland was nevre knicth That betere held the lond to ricth. Of his bodi ne havede he eyr Bute a mayden swithe fayr, That was so yung that sho ne couthee Gon on fote ne speke wit mouthe. Than him tok an ivel strong, That he wel wiste and underfong That his deth was comen him on And saide, “Crist, wat shal I don? Louerd, wat shal me to rede? I wot ful wel ich have mi mede. Hw shal now my douhter fare? Of hire have ich michel kare; Sho is mikel in my thouth - Of meself is me rith nowt. No selcouth is thou me be wo: Sho ne can speke ne sho kan go. Yif scho couthe on horse ride, And a thousande men bi hire syde, And sho were comen intil helde And Engelond sho couthe welde, And don hem of thar hire were queme, And hire bodi couthe yeme, Ne wolde me nevere ivele like, Ne though ich were in heveneriche.” Quanne he havede this pleinte maked, Therafter stronglike quaked. He sende writes sone onon After his erles evereichon; And after hise baruns, riche and poure, Fro Rokesburw al into Dovere, That he shulden comen swithe Til him, that was ful unblithe, To that stede ther he lay In harde bondes nicth and day. He was so faste wit yvel fest That he ne mouthe haven no rest, He ne mouthe no mete hete, Ne he ne mouchte no lythe gete, Ne non of his ivel that couthe red - Of him ne was nouth buten ded. Alle that the writes herden Sorful and sori til him ferden; He wrungen hondes and wepen sore And yerne preyden Cristes hore - That He wolde turnen him Ut of that yvel that was so grim. Thanne he weren comen alle Bifor the king into the halle, At Winchestre ther he lay, “Welcome,” he sayde, “be ye ay! Ful michel thank kan I you That ye aren comen to me now.” Quanne he weren alle set, And the king aveden igret, He greten and gouleden and gouven hem ille, And he bad hem alle been stille And seyde that greting helpeth nouth, “For al to dede am ich brouth. Bute now ye sen that I shal deye, Now ich wille you alle preye Of mi douther, that shal be Yure levedi after me, Wo may yemen hire so longe, Bothen hire and Engelonde, Til that she be wman of helde And that she mowe hir yemen and welde?” He answereden and seyden anon, Bi Crist and bi Seint Jon, That th erl Godrigh of Cornwayle Was trewe man wituten faile, Wis man of red, wis man of dede, And men haveden of him mikel drede - “He may hire altherbest yeme, Til that she mowe wel ben quene.” The king was payed of that rede. A wol fair cloth bringen he dede, And thereon leyde the messebok, The caliz, and the pateyn ok, The corporaus, the messe-gere. Theron he garte the erl swere That he sholde yemen hire wel, Withuten lac, wituten tel, Til that she were twelf winter hold And of speche were bold, And that she couthe of curteysye, Gon and speken of lovedrurye, And til that she loven muthe Wom so hire to gode thoucte; And that he shulde hire yeve The beste man that micthe live - The beste, fayreste, the strangest ok; That dede he him sweren on the bok, And thanne shulde he Engelond Al bitechen into hire hond. Quanne that was sworn on his wise, The king dede the mayden arise, And the erl hire bitaucte And al the lond he evere awcte - Engelonde, everi del - And preide he shulde yeme hire wel. The king ne moucte don no more, But yerne preyede Godes ore, And dede him hoslen wel and shrive, I wot fif hundred sithes and five, And ofte dede him sore swinge And wit hondes smerte dinge So that the blod ran of his fleys, That tendre was and swithe neys. He made his quiste swithe wel And sone gaf it everil del. Wan it was goven, ne micte men finde So mikel men micte him in winde, Of his in arke ne in chiste, In Engelond, that noman wiste; For al was yoven, faire and wel, That him was leved no catel. Thanne he havede been ofte swngen, Ofte shriven and ofte dungen, “In manus tuas, Louerde,” he seyde, Her that he the speche leyde, To Jesu Crist bigan to calle And deyede biforn his heymen alle. Than he was ded, there micte men se The meste sorwe that micte be: Ther was sobbing, siking, and sor, Handes wringing and drawing bi hor. Alle greten swithe sore, Riche and poure that there wore, And mikel sorwe haveden alle - Levedyes in boure, knictes in halle. Quan that sorwe was somdel laten And he haveden longe graten, Belles deden he sone ringen, Monkes and prestes messe singen; And sauteres deden he manie reden, That God self shulde his soule leden Into hevene biforn his Sone, And ther wituten hende wone. Than he was to the erthe brouth, The riche erl ne foryat nouth That he ne dede al Engelond Sone sayse intil his hond, And in the castels leth he do The knictes he mighte tristen to, And alle the Englis dede he swere That he shulden him ghod fey beren: He yaf alle men that god thoucte, Liven and deyen til that him moucte, Til that the kinges dowter wore Twenti winter hold and more. Thanne he havede taken this oth Of erles, baruns, lef and loth, Of knictes, cherles, fre and thewe, Justises dede he maken newe Al Engelond to faren thorw Fro Dovere into Rokesborw. Schireves he sette, bedels, and greyves, Grith sergeans with longe gleyves, To yemen wilde wodes and pathes Fro wicke men that wolde don scathes, And forto haven alle at his cri, At his wille, at hise merci, That non durste ben him ageyn - Erl ne barun, knict ne sweyn. Wislike for soth was him wel Of folc, of wepne, of catel: Sothlike, in a lite thrawe Al Engelond of him stod awe - Al Engelond was of him adrad, So his the beste fro the gad. The kinges douther bigan thrive And wex the fairest wman on live. Of alle thewes was she wis That gode weren and of pris. The mayden Goldeboru was hoten; For hire was mani a ter igroten. Quanne the Erl Godrich him herde Of that mayden - hw wel she ferde, Hw wis sho was, hw chaste, hw fayr, And that sho was the rithe eyr Of Engelond, of al the rike; Tho bigan Godrich to sike, And seyde, “Wether she sholde be Quen and levedi over me? Hwether sho sholde al Engelond And me and mine haven in hire hond? Datheit hwo it hire thave! Shal sho it nevere more have. Sholde ic yeve a fol, a therne, Engelond, thou sho it yerne? Datheit hwo it hire yeve Evere more hwil I live! She is waxen al to prud, For gode metes and noble shrud, That hic have yoven hire to offte; Hic have yemed hire to softe. Shal it nouth ben als sho thenkes: Hope maketh fol man ofte blenkes. Ich have a sone, a ful fayr knave; He shal Engelond al have! He shal king, he shal ben sire, So brouke I evere mi blake swire!” Hwan this trayson was al thouth, Of his oth ne was him nouth. He let his oth al overga. Therof he yaf he nouth a stra, Bute sone dede hire fete, Er he wolde heten ani mete, Fro Winchestre ther sho was, Also a wicke traytur Judas, And dede leden hire to Dovre, That standeth on the seis oure, And therhinne dede hire fede Pourelike in feble wede. The castel dede he yemen so That non ne micte comen hire to Of hire frend, with to speken, That hevere micte hire bale wreken. Of Goldeboru shul we now laten, That nouth ne blinneth forto graten Ther sho liggeth in prisoun. Jesu Crist, that Lazarun To live broucte fro dede bondes, He lese hire wit Hise hondes! And leve sho mote him yse Heye hangen on galwe tre That hire haved in sorwe brouth, So as sho ne misdede nouth. Say we now forth in hure spelle! In that time, so it bifelle, Was in the lond of Denemark A riche king and swythe stark. The name of him was Birkabeyn; He havede mani knict and sweyn; He was fayr man and wict, Of bodi he was the beste knicth That evere micte leden uth here, Or stede on ride or handlen spere. Thre children he havede bi his wif - He hem lovede so his lif. He havede a sone, douhtres two, Swithe fayre, as fel it so. He that wile non forbere, Riche ne poure, king ne kaysere, Deth him tok than he best wolde Liven, but hyse dayes were fulde, That he ne moucte no more live, For gold ne silver ne for no gyve. Hwan he that wiste, rathe he sende After prestes, fer an hende - Chanounes gode and monkes bothe, Him for to wisse and to rede, Him for to hoslen an for to shrive, Hwil his bodi were on live. Hwan he was hosled and shriven, His quiste maked and for him gyven, Hise knictes dede he alle site, For thoru hem he wolde wite Hwo micte yeme his children yunge Til that he kouthen speken wit tunge, Speken and gangen, on horse riden, Knictes and sweynes by here siden. He spoken theroffe and chosen sone A riche man that under mone, Was the trewest, that he wende - Godard, the kinges owne frende - And seyden he moucthe hem best loke Yif that he hem undertoke, Til hise sone mouthe bere Helm on heved and leden ut here, In his hand a spere stark, And king been maked of Denemark. He wel trowede that he seyde, And on Godard handes leyde; And seyde, “Here biteche I thee Mine children alle thre, Al Denemark and al mi fe, Til that mi sone of helde be, But that ich wille that thou swere On auter and on messe gere, On the belles that men ringes, On messe bok the prest on singes, That thou mine children shalt wel yeme, That hire kin be ful wel queme, Til mi sone mowe ben knicth. Thanne biteche him tho his ricth: Denemark and that ther til longes - Casteles and tunes, wodes and wonges.” Godard stirt up and swor al that The king him bad, and sithen sat Bi the knictes that ther ware, That wepen alle swithe sare For the king that deide sone. Jesu Crist, that makede mone On the mirke nith to shine, Wite his soule fro helle pine; And leve that it mote wone In heveneriche with Godes Sone! Hwan Birkabeyn was leyd in grave, The erl dede sone take the knave, Havelok, that was the eir, Swanborow, his sister, Helfled, the tother, And in the castel dede he hem do, Ther non ne micte hem comen to Of here kyn, ther thei sperd were. Ther he greten ofte sore Bothe for hunger and for kold, Or he weren thre winter hold. Feblelike he gaf hem clothes; He ne yaf a note of hise othes - He hem clothede rith ne fedde, Ne hem ne dede richelike bebedde. Thanne Godard was sikerlike Under God the moste swike That evre in erthe shaped was. Withuten on, the wike Judas. Have he the malisun today Of alle that evre speken may - Of patriark and of pope, And of prest with loken kope, Of monekes and hermites bothe, And of the leve Holi Rode That God himselve ran on blode! Crist warie him with His mouth! Waried wrthe he of north and suth, Offe alle men that speken kunne, Of Crist that made mone and sunne! Thanne he havede of al the lond Al the folk tilled intil his hond, And alle haveden sworen him oth, Riche and poure, lef and loth, That he sholden hise wille freme And that he shulde him nouth greme, He thouthe a ful strong trechery, A trayson and a felony, Of the children for to make - The devel of helle him sone take! Hwan that was thouth, onon he ferde To the tour ther he woren sperde, Ther he greten for hunger and cold. The knave, that was sumdel bold, Kam him ageyn, on knes him sette, And Godard ful feyre he ther grette. And Godard seyde, “Wat is yw? Hwi grete ye and goulen now?" “For us hungreth swithe sore” - Seyden he, “we wolden more: We ne have to hete, ne we ne have Her inne neyther knith ne knave That yeveth us drinke ne no mete, Halvendel that we moun ete - Wo is us that we weren born! Weilawei! nis it no korn That men micte maken of bred? Us hungreth - we aren ney ded!" Godard herde here wa, Ther-offe yaf he nouth a stra, But tok the maydnes bothe samen, Al so it were up on hiis gamen, Al so he wolde with hem leyke That weren for hunger grene and bleike. Of bothen he karf on two here throtes, And sithen hem al to grotes. Ther was sorwe, wo-so it sawe, Hwan the children by the wawe Leyen and sprawleden in the blod. Havelok it saw and therbi stod - Ful sori was that sely knave. Mikel dred he mouthe have, For at hise herte he saw a knif For to reven him hise lyf. But the knave, that litel was, He knelede bifor that Judas, And seyde, “Louerd, mercy now! Manrede, louerd, biddi you: Al Denemark I wile you yeve, To that forward thu late me live. Here hi wile on boke swere That nevremore ne shal I bere Ayen thee, louerd, sheld ne spere, Ne other wepne that may you dere. Louerd, have merci of me! Today I wile fro Denemark fle, Ne neveremore comen agheyn! Sweren I wole that Bircabein Nevere yete me ne gat.” Hwan the devel herde that, Sumdel bigan him for to rewe; Withdrow the knif, that was lewe Of the seli children blod. Ther was miracle fair and god That he the knave nouth ne slou, But for rewnesse him witdrow - Of Avelok rewede him ful sore, And thoucte he wolde that he ded wore, But on that he nouth wit his hend Ne drepe him nouth, that fule fend! Thoucte he als he him bi stod, Starinde als he were wod, “Yif I late him lives go, He micte me wirchen michel wo - Grith ne get I neveremo; He may me waiten for to slo. And if he were brouct of live, And mine children wolden thrive, Louerdinges after me Of al Denemark micten he be. God it wite, he shal ben ded - Wile I taken non other red! I shal do casten him in the she, Ther I wile that he drench be, Abouten his hals an anker god, Thad he ne flete in the flod.” Ther anon he dede sende After a fishere that he wende That wolde al his wille do, And sone anon he seyde him to: “Grim, thou wost thu art my thral; Wilte don my wille al That I wile bidden thee? Tomorwen shal maken thee fre, And aucte thee yeven and riche make, Withthan thu wilt this child take And leden him with thee tonicht, Than thou sest the monelith, Into the se and don him therinne. Al wile I taken on me the sinne.” Grim tok the child and bond him faste, Hwil the bondes micte laste, That weren of ful strong line. Tho was Havelok in ful strong pine - Wiste he nevere her wat was wo! Jhesu Crist, that makede go The halte and the doumbe speken, Havelok, thee of Godard wreke! Hwan Grim him havede faste bounden, And sithen in an eld cloth wnden, He thriste in his muth wel faste A kevel of clutes ful unwraste, That he mouthe speke ne fnaste, Hwere he wolde him bere or lede. Hwan he havede don that dede, Hwat the swike him havede he yede That he shulde him forth lede And him drinchen in the se - That forwarde makeden he - In a poke, ful and blac, Sone he caste him on his bac, Ant bar him hom to hise cleve, And bitaucte him Dame Leve And seyde, “Wite thou this knave, Al so thou wit mi lif save! I shal dreinchen him in the se; For him shole we ben maked fre, Gold haven ynow and other fe: That havet mi louerd bihoten me.” Hwan Dame Leve herde that, Up she stirte and nouth ne sat, And caste the knave so harde adoun That he crakede ther his croune Ageyn a gret ston ther it lay. Tho Havelok micte sei, “Weilawei, That evere was I kinges bern - That him ne havede grip or ern, Leoun or wlf, wlvine or bere, Or other best that wolde him dere!" So lay that child to middel nicth, That Grim bad Leve bringen lict, For to don on his clothes: “Ne thenkestu nowt of mine othes That ich have mi louerd sworen? Ne wile I nouth be forloren. I shal beren him to the se - Thou wost that hoves me - And I shal drenchen him therinne; Ris up swithe an go thu binne, And blow the fir and lith a kandel.” Als she shulde hise clothes handel On for to don and blawe the fir, She saw therinne a lith ful shir, Al so brith so it were day, Aboute the knave ther he lay. Of hise mouth it stod a stem Als it were a sunnebem; Al so lith was it therinne So ther brenden cerges inne. “Jesu Crist!” wat Dame Leve, “Hwat is that lith in ure cleve? Ris up, Grim, and loke wat it menes! Hwat is the lith, as thou wenes?" He stirten bothe up to the knave For man shal god wille have, Unkeveleden him and swithe unbounden, And sone anon him funden, Als he tirveden of his serk, On hise rith shuldre a kynmerk, A swithe brith, a swithe fair. “Goddot!” quath Grim, “this ure eir, That shal louerd of Denemark! He shal ben king, strong and stark; He shal haven in his hand Al Denemark and Engeland. He shal do Godard ful wo; He shal him hangen or quik flo, Or he shal him al quic grave. Of him shal he no merci have.” Thus seide Grim and sore gret, And sone fel him to the fet, And seide, “Louerd, have mercy Of me and Leve, that is me bi! Louerd, we aren bothe thine - Thine cherles, thine hine. Louerd, we sholen thee wel fede Til that thu cone riden on stede, Til that thu cone ful wel bere Helm on heved, sheld and spere. He ne shall nevere wite, sikerlike, Godard, that fule swike. Thoru other man, louerd, than thoru thee Shal I nevere freman be. Thou shalt me, louerd, fre maken, For I shal yemen thee and waken - Thoru thee wile I fredom have.” Tho was Haveloc a blithe knave! He sat him up and cravede bred, And seide, “Ich am ney ded, Hwat for hunger, wat for bondes That thu leidest on min hondes, And for kevel at the laste, That in my mouth was thrist faste. I was ther with so harde prangled That I was ther with ney strangled!" “Wel is me that thou mayth hete! Goddoth!” quath Leve, “I shal thee fete Bred an chese, butere and milk, Pastees and flaunes - al with swilk Shole we sone thee wel fede, Louerd, in this mikel nede. Soth it is that men seyt and swereth: 'Ther God wile helpen, nouth ne dereth.'” Thanne sho havede brouth the mete, Haveloc anon bigan to ete Grundlike, and was ful blithe. Couthe he nouth his hunger mithe. A lof he het, I woth, and more, For him hungrede swithe sore. Thre dayes ther biforn, I wene, Et he no mete - that was wel sene! Hwan he havede eten and was fed, Grim dede maken a ful fayr bed, Unclothede him and dede him therinne, And seyde, “Slep, sone, with muchel winne! Slep wel faste and dred thee nouth - Fro sorwe to joie art thu brouth.” Sone so it was lith of day, Grim it undertok the wey To the wicke traitour Godard That was of Denemark a stiward And saide, “Louerd, don ich have That thou me bede of the knave: He is drenched in the flod, Abouten his hals an anker god - He is witerlike ded. Eteth he nevremore bred: He lith drenched in the se. Yif me gold and other fe, That I mowe riche be, And with thi chartre make fre; For thu ful wel bihetet me Thanne I last spak with thee.” Godard stod and lokede on him Thoruthlike, with eyne grim, And seyde, “Wiltu ben erl? Go hom swithe, fule drit-cherl; Go hethen and be everemore Thral and cherl als thou er wore - Shaltu have non other mede; For litel I do thee lede To the galwes, so God me rede! For thou haves don a wicke dede. Thou mait stonden her to longe, Bute thou swithe hethen gonge!” Grim thoucte to late that he ran Fro that traytour, that wicke man, And thoucte, “Wat shal me to rede? Wite he him on live he wile bethe Heye hangen on galwe tre. Betere us is of londe to fle, And berwen bothen ure lives, And mine children and mine wives.” Grim solde sone al his corn, Shep with wolle, neth with horn, Hors and swin, geet with berd, The gees, the hennes of the yerd - Al he solde that outh douthe, That he evre selle moucte; And al he to the peni drou. Hise ship he greythede wel inow; He dede it tere an ful wel pike That it ne doutede sond ne krike; Therinne dide a ful god mast, Stronge kables and ful fast, Ores gode an ful god seyl - Therinne wantede nouth a nayl, That evere he sholde therinne do. Hwan he havedet greythed so, Havelok the yunge he dede therinne, Him and his wif, hise sones thrinne, And hise two doutres that faire wore. And sone dede he leyn in an ore, And drou him to the heye see, There he mith altherbeste fle. Fro londe woren he bote a mile, Ne were it nevere but ane hwile That it ne bigan a wind to rise Out of the north men calleth “bise," And drof hem intil Engelond, That al was sithen in his hond, His, that Havelok was the name; But or he havede michel shame, Michel sorwe and michel tene, And yete he gat it al bidene; Als ye shulen now forthward lere, Yf that ye wilen therto here. In Humber Grim bigan to lende, In Lindeseye, rith at the north ende. Ther sat his ship upon the sond; But Grim it drou up to the lond; And there he made a litel cote To him and to hise flote. Bigan he there for to erthe, A litel hus to maken of erthe, So that he wel thore were Of here herboru herborwed there. And for that Grim that place aute, The stede of Grim the name laute, So that Grimesbi it calleth alle That theroffe speken alle; And so shulen men callen it ay, Bitwene this and Domesday. Grim was fishere swithe god, And mikel couthe on the flod - Mani god fish therinne he tok, Bothe with neth and with hok. He tok the sturgiun and the qual, And the turbut and lax withal; He tok the sele and the hwel - He spedde ofte swithe wel. Keling he tok and tumberel, Hering and the makerel, The butte, the schulle, the thornebake. Gode paniers dede he make, On til him and other thrinne Til hise sones to beren fishe inne, Up o londe to selle and fonge - Forbar he neyther tun ne gronge That he ne to yede with his ware. Kam he nevere hom hand-bare, That he ne broucte bred and sowel In his shirte or in his cowel, In his poke benes and korn - Hise swink he havede he nowt forlorn. And hwan he took the grete lamprey, Ful wel he couthe the rithe wei To Lincolne, the gode boru; Ofte he yede it thoru and thoru, Til he havede wol wel sold And therfore the penies told. Thanne he com thenne he were blithe, For hom he brouthe fele sithe Wastels, simenels with the horn, His pokes fulle of mele and korn, Netes flesh, shepes and swines; And hemp to maken of gode lines, And stronge ropes to hise netes, In the se weren he ofte setes. Thusgate Grim him fayre ledde: Him and his genge wel he fedde Wel twelf winter other more. Havelok was war that Grim swank sore For his mete, and he lay at hom - Thouthe, “Ich am now no grom! Ich am wel waxen and wel may eten More than evere Grim may geten. Ich ete more, bi God on live, Than Grim an hise children five! It ne may nouth ben thus longe. Goddot! I wile with hem gange For to leren sum god to gete. Swinken ich wolde for my mete - It is no shame for to swinken! The man that may wel eten and drinken Thar nouth ne have but on swink long - To liggen at hom it is ful strong. God yelde him, ther I ne may, That haveth me fed to this day! Gladlike I wile the paniers bere - Ich woth ne shal it me nouth dere, They ther be inne a birthene gret Al so hevi als a neth. Shal ich nevere lengere dwelle - Tomorwen shal ich forth pelle.” On the morwen, hwan it was day, He stirt up sone and nouth ne lay, And cast a panier on his bac, With fish giveled als a stac. Al so michel he bar him one, So he foure, bi mine mone! Wel he it bar and solde it wel; The silver he brouthe hom ilk del, Al that he therfore tok - Withheld he nouth a ferthinges nok. So yede he forth ilke day That he nevere at home lay - So wolde he his mester lere. Bifel it so a strong dere Bigan to rise of korn of bred, That Grim ne couthe no god red, Hw he sholde his meiné fede; Of Havelok havede he michel drede, For he was strong and wel mouthe ete More thanne evere mouthe be gete; Ne he ne mouthe on the se take Neyther lenge ne thornbake, Ne non other fish that douthe His meyné feden with he mouthe. Of Havelok he havede kare, Hwilgat that he micthe fare. Of his children was him nouth; On Havelok was al hise thouth, And seyde, “Havelok, dere sone, I wene that we deye mone For hunger, this dere is so strong, And hure mete is uten long. Betere is that thu henne gonge Than thu here dwelle longe - Hethen thou mayt gangen to late; Thou canst ful wel the ricthe gate To Lincolne, the gode boru - Thou havest it gon ful ofte thoru. Of me ne is me nouth a slo. Betere is that thu thider go, For ther is mani god man inne; Ther thou mayt thi mete winne. But wo is me thou art so naked, Of mi seyl I wolde thee were maked A cloth thou mithest inne gongen, Sone, no cold that thu ne fonge.” He tok the sheres of the nayl And made him a covel of the sayl, And Havelok dide it sone on. Havede he neyther hosen ne shon, Ne none kines other wede: To Lincolne barfot he yede. Hwan he cam ther, he was ful wil - Ne havede he no frend to gangen til. Two dayes ther fastinde he yede, That non for his werk wolde him fede. The thridde day herde he calle: “Bermen, bermen, hider forth alle!" Poure that on fote yede Sprongen forth so sparke on glede, Havelok shof dun nyne or ten Rith amidewarde the fen, And stirte forth to the kok, Ther the erles mete he tok That he bouthe at the brigge: The bermen let he alle ligge, And bar the mete to the castel, And gat him there a ferthing wastel. Thet other day kepte he ok Swithe yerne the erles kok, Til that he say him on the brigge, And bi him many fishes ligge. The herles mete havede he bouth Of Cornwalie and kalde oft: “Bermen, bermen, hider swithe!" Havelok it herde and was ful blithe That he herde “bermen” calle. Alle made he hem dun falle That in his gate yeden and stode - Wel sixtene laddes gode. Als he lep the kok til, He shof hem alle upon an hyl - Astirte til him with his rippe And bigan the fish to kippe. He bar up wel a carte lode Of segges, laxes, of playces brode, Of grete laumprees and of eles. Sparede he neyther tos ne heles Til that he to the castel cam, That men fro him his birthene nam. Than men haveden holpen him doun With the birthene of his croun, The kok stod and on him low, And thoute him stalworthe man ynow, And seyde, “Wiltu ben wit me? Gladlike wile ich feden thee: Wel is set the mete thu etes, And the hire that thu getes!" "Goddot!” quoth he, “leve sire, Bidde ich you non other hire, But yeveth me inow to ete - Fir and water I wile you fete, The fir blowe and ful wele maken; Stickes kan ich breken and kraken, And kindlen ful wel a fyr, And maken it to brennen shir. Ful wel kan ich cleven shides, Eles to turven of here hides; Ful wel kan ich dishes swilen, And don al that ye evere wilen.” Quoth the kok, “Wile I no more! Go thu yunder and sit thore, And I shal yeve the ful fair bred, And made the broys in the led. Sit now doun and et ful yerne - Datheit hwo the mete werne!" Havelok sette him dun anon Al so stille als a ston, Til he havede ful wel eten; Tho havede Havelok fayre geten. Hwan he havede eten inow, He kam to the wele, water up drow, And filde ther a michel so - Bad he non ageyn him go, But bitwen his hondes he bar it in, Al him one, to the kichin. Bad he non him water to fett, Ne fro brigge to bere the mete. He bar the turves, he bar the star, The wode fro the brigge he bar, Al that evere shulden he nytte, Al he drow and al he citte - Wolde he nevere haven rest More than he were a best. Of alle men was he mest meke, Lauhwinde ay and blithe of speke; Evere he was glad and blithe - His sorwe he couthe ful wel mithe. It ne was non so litel knave For to leyken ne for to plawe, That he ne wolde with him pleye. The children that yeden in the weie Of him he deden al here wille, And with him leykeden here fille. Him loveden alle, stille and bolde, Knictes, children, yunge and holde - Alle him loveden that him sowen, Bothen heye men and lowe. Of him ful wide the word sprong, Hw he was mikel, hw he was strong, Hw fayr man God him havede maked, But on that he was almest naked: For he ne havede nouth to shride But a kovel ful unride, That was ful and swithe wicke; Was it nouth worth a fir-sticke. The cok bigan of him to rewe And bouthe him clothes al spannewe: He bouthe him bothe hosen and shon, And sone dide him dones on. Hwan he was clothed, osed, and shod, Was non so fayr under God, That evere yete in erthe were, Non that evere moder bere; It was nevere man that yemede In kinneriche that so wel semede King or cayser for to be, Than he was shrid, so semede he; For thanne he weren alle samen At Lincolne at the gamen, And the erles men woren al thore, Than was Havelok bi the shuldren more Than the meste that ther kam: In armes him noman nam That he doune sone ne caste. Havelok stod over hem als a mast; Als he was heie, als he was long, He was bothe stark and strong - In Engelond non hise per Of strengthe that evere kam him ner. Als he was strong, so was he softe; They a man him misdede ofte, Neveremore he him misseyde, Ne hond on him with yvele leyde. Of bodi was he mayden clene; Nevere yete in game, ne in grene, With hire ne wolde he leyke ne lye, No more than it were a strie. |

Pay attention to me, good men, Wives, maidens, and everyone else To a tale that I will tell you For whoever wants to stay and hear it. The story is about Havelock, Who when he was little went half-naked. Havelock was a good man, The best in every company. He was the bravest man in need Who might ride on any steed! So that you may hear me, And so that you might know the tale, At the beginning of our story, Fill me a cup of your best ale. And let’s drink, while I tell it, That Christ might shield us all from Hell! May Christ protect us forever So that we might come to Him, And, so that it may be so, Let us praise the Lord! Here I'll begin the rhyme, And may Christ give us a good end! The rhyme is about Havelock, A steady man to have in a group. He was the hardiest man in need Who might ride on any steed. There was a king in days of old, Who in his time made good laws And observed them well. He was loved by young, loved by old, By earl and baron, vassal and retainer, Knight, bondsman, and servant, Widows, maidens, priests, and clerks, And all for his good works. He loved God with all his might, And the holy church, and truth and justice. He loved all righteous men, And everywhere had them at his call. He made traitors and robbers fail, And hated them like men hate bitter drink. Outlaws and thieves were bound, Any that he might find, And hung high on the gallows tree. He took neither gold nor any bribe from them. In that time a man who bore Upwards of fifty pounds, I guess, or more, Of red gold on his back, In a pouch, white or black, Would not meet anyone who would mistreat him, Or lay hands on him with evil intent. Back then merchants could travel Throughout England with their wares, And boldly buy and sell, Anywhere they wanted to stay. In fine towns and in the countryside They would not meet anyone to cause them harm Who would not soon be brought to ruin, Made poor, and reduced to nothing for it. England was at ease then. There was much to praise about such a king Who held England in such peace. Christ in Heaven was with him; He was England’s bloom! There was no lord as far as Rome Who dared to bring to his people Hunger, invasion, or wicked causes. When the king defeated his enemies, He made them lurk and creep in corners. They all hid themselves and kept quiet, And did all his heart’s will. But he loved justice above all things. No man could corrupt him into wrong, Not for silver or for gold, So faithful was he to his soul. To the orphaned he was their protector; Whoever did them wrong or harm, No matter if they were a cleric or knight, Was soon brought to justice by him. And as for anyone who did widows wrong, There was no knight so strong That he wouldn't soon have him thrown Into fetters and fasten them tightly. And as for whoever shamed a maiden By her body, or brought her into blame, Unless it was by her consent, He made him lose some of his limbs. The king was the best knight in need Who might ever ride on a steed, Or hold a weapon, or lead out an army. He was never so afraid of any knights That he would not spring forth like sparks from fire And let them know by the deeds of his hand How he could be victorious with a weapon. With others he took their horses or fine clothes, Or made them quickly spread their hands, And cry loudly, “Mercy, Lord!" He was generous and by no means stingy. He never had bread so good On his table or a morsel so fine That he would not give it to feed The poor who went on foot, In order to receive from Him the reward That He bled on the Cross for us to have— Christ, who can guide and protect all Who ever live in any land. The king was called Athelwold. With speech and weapons he was bold. In England there was never a knight Who better held the land in justice. But he had fathered no heir Except for a very fair maiden Who was so young that she could not Walk or speak with her mouth. Then he was taken by a violent illness, So that he knew well and understood That his death was coming. And he said, “Christ, what should I do? Lord, how should I be advised? I know full well I will have my reward, But how will my daughter fare? I have great concerns about her And she is much in my thoughts; I have no worries about myself. It is no wonder for You that I am anxious. She cannot speak, nor can she walk. If she knew how to ride a horse, With a thousand men by her side, And she came to age, She could rule England And do to others as she pleased And would know how to rule her body. I would otherwise never be at ease, Even if I were in Heaven’s realm.” When he had made this plea, He shivered strongly after. At once he sent out writs To his earls, each one of them, And to his barons, rich and poor, From Roxburgh through to Dover, That they should come quickly To him, as he was very ill, To the place where he lay In hard bonds, night and day. He was so trapped in death’s grip That he could have no rest. He could take no food, Nor might he have any comfort. No one could advise him in his gloom, For he was little more than dead. All who obeyed the writs Traveled to him in sorrow and grief. They wrung their hands and wept bitterly, And earnestly prayed for Christ’s grace, That He would release him From his illness which was so grim. When they had all come Before the king in the hall Where he lay at Winchester, “You are forever welcome!” he said. “I give you great thanks That you have come to me now.” When they were all seated And the king had greeted them, They wept and wailed and mourned, Until the king asked that they all be quiet, And said, “Crying does nothing to help, For I am brought to death. But now that you see that I am dying, I will ask you all now About my daughter, who will be Your sovereign lady after me. Who will guard her for a time, Both her and England, Until she is a woman of age, And can take care of and guide herself?" They answered and said at once, By Christ and by Saint John, That Earl Godrich of Cornwall Was a faithful man, without doubt, A wise man in counsel, a wise man in deed, And men had great deference for him. “He can best take care of her, Until she may be queen in full.” The king was pleased with that advice. He had a beautiful woolen cloth brought, And laid the mass-book on it, The chalice, and the Eucharist plate as well, And the communion cloth and vestments. Then he made the earl swear That he would protect her well, Without fail, without reproach, Until she was twelve years old And she was confident in speech And could understand court etiquette And the manners and speech of courtship, And until she might love Whoever she felt seemed best to her; And that he would give to her The highest man who might live, The best, fairest, and the strongest as well. All this the king had him swear on the book. And then he would bestow All of England into her hand. When that was sworn in this way, The king had the maiden rise, And committed her to the earl Along with all the land he ever owned, Every part of England, And prayed that he would keep her well. The king could do no more, But earnestly prayed for God’s grace And took communion and confession, Five hundred and five times, I know, And repeatedly scourged himself severely, And beat himself painfully with his own hands So that the blood ran from his flesh, Which had been so tender and soft. He made his will out carefully, And soon after had every part affirmed. When it was executed, no man could find So much as a burial sheet to wrap him in Of his in any coffer or chest That anyone knew of in England. For everything was disposed of, fair and clear, So that no possessions were left to him. When he had been continually scourged, Confessed, and beaten, He said, “Into your hands, Lord," And set aside his words then. He began to call on Jesus Christ, And died before all of his noblemen. When he was dead, men could see The greatest sorrow that might be. There was sobbing, sighing, and grief, Hands wringing, and clutching of hair. Everyone there wept bitterly, All the rich and poor that were there, And all had great sorrow, Ladies in chambers, and knights in the hall. When the mourning had subsided somewhat, And they had wept a long time, They soon after rang bells, Monks and priests sang mass, And they read out many psalm books, Praying that God Himself would lead his soul Into Heaven before His Son To live with Them there without end. After the king was delivered to the earth, The powerful earl overlooked nothing Until he soon had all of England Seized into his hand. He placed in the castles The knights which he could trust, And he forced all the English to swear That they would act in good faith to him. He gave men what seemed right to him, To live and die as he saw fit Until the king’s daughter was Twenty years old or more. When the earl had received this oath From earls and barons, fair and foul, From knights and laborers, free and bound, He had new justices appointed To travel through all England From Dover into Roxburgh. He ordained sheriffs, church officers, and reeves, And peace sergeants with long lances, To guard the wild woods and paths From wicked men who would commit harm, And to have all at his beck and call, At his will, and at his mercy, So that no one would dare be against him, Not earl, baron, knight, or peasant. To be sure, in truth, he had an abundance Of people, weapons, and possessions. Truly, in a short while, All of England stood in awe of him; All of England was afraid of him, Like the cattle fears the prod. The king’s daughter began to flower And grew into the fairest woman alive. She was wise in all manners That were good and were cherished. The maiden was called Goldeboro, And for her many a tear would be wept. When Earl Godrich heard about the maiden, How well she was faring, How wise she was, how chaste, how fair, And how she was the rightful heir Of England, of all the kingdom, Then Godrich began to complain, And griped, “Why should she be Queen and lady over me? Why should she have all England, And me and what’s mine, in her hand? Damn whoever lets her have it! She will never see it happen. Should I give a fool, a serving wench, England, just because she wants it? Damn whoever hands it to her While I'm alive! She has grown too proud With the good food and royal clothes That I have too often given her. I have pampered her too well! It is not going to end as she thinks. Hope often makes a foolish man blind. I have a son, a handsome boy; He shall have all England! He shall be king! He will be sire, So long as I have a head on these shoulders!" When this treason was all thought out, His oath no longer meant anything to him. He let his promise go entirely, And after then did not care a straw for it. But before he would eat another thing, He ordered for her to be fetched From where she was at Winchester, And just like a wicked traitor Judas, He had her sent to Dover, Which stands on the seashore, And had her kept there In poverty and in wretched clothes. He had the castle guarded So that none of her friends Might come to speak with her, Anyone who might ever avenge her wrong. We will now leave Goldboro for a while, Who laments without ceasing, Where she lies in prison. May Jesus Christ, who brought Lazarus To life from the bonds of death, Release her with His hands! And grant that she might see him Hanging high on the gallows tree, The man who brought her into sorrow, Even though she had done no wrong. Let us continue forth in our story. In that time, as it so happened, In the land of Denmark there was A rich and very powerful king. His name was Birkabeyn. He had many knights and attendants; He was a handsome and valiant man. He was the best knight in body Who ever might command an army, Or ride a horse, or handle a spear. He had three children by his wife, And he loved them as much as his life. He had a son and two daughters Who were, as it happened, very beautiful. But death, who spares no one, Neither rich nor poor, king nor emperor, Took him when he would rather live; But his days were complete, So that he could no longer remain, Not for gold, silver, or any gift. When the king realized this he quickly sent For priests from near and far, Canon priests and monks as well, To counsel and advise him, And to confess and absolve him While his body was still alive. When he was given the sacraments, With his will made and given for him, He had all his knights seated, For through them he would know Who might take care of his young children Until they could speak with their tongues, Walk and talk, and rise horses With knights and attendants by their sides. He spoke of this matter and soon chose A powerful man who was the truest Under the moon that he knew— Godard, the king’s own friend— And said he might care for them best If he committed himself to them, Until his son could bear A helmet on his head and lead an army, With a strong spear in his hand, And be made king of Denmark. The king believed what Godard said And laid hands on him And said, “I here entrust to you Each of my three children, All Denmark, and all my properties, Until my son is of age. But I want you to swear On the altar and the church vestments, On the bells that men ring, And on the hymnal from which the priests sing, That you will protect my children well, So that their family will be satisfied, Until my son can be a knight. Then endow him with his right: Denmark and all that belongs to it, Castles, towns, woods, and fields.” Godard rose and swore everything That the king asked him, and afterward sat With the knights who were there, Who were all weeping very bitterly For the king, who soon died. May Jesus Christ, who makes the moon Shine on the darkest night, Protect his soul from Hell’s pains, And grant that it may dwell In Heaven with God’s Son! When Birkabeyn was laid in his grave, The earl immediately took the boy, Havelock, who was the heir, Swanboro, his sister, and Hefled, the other, And he had them put in the castle, Where none might come to them From their relatives; there they were kept. They cried there miserably, Both from hunger and the cold, Before they were even three years old. He gave them clothes grudgingly; He didn't care a nut about his oaths! He didn't clothe or feed them properly, Or provide them with a royal bedroom. In that time Godard was surely The worst traitor under God Who was ever created on earth, Except for one, the wicked Judas. May he have the curse today Of all who might ever pronounce them, Of patriarchs and popes, And of priests with buttoned cloaks, Of both monks and hermits, And by the beloved Holy Cross That God Himself bled upon. May Christ condemn him with His mouth! May he be reviled from north to south, By all men who can speak, By Christ, who made the moon and sun. For after then he had all the land, And all the folk, tilled into his hand, And all had to swear him oaths, Rich and poor, fair and foul, That they would perform his will, And that they would not oppose him. He worked up a villainous treachery, A treason and a felony, To carry out on the children. May the devil soon take him to Hell! When that was planned, he went on To the tower where they were kept, Where they wept for hunger and cold. The boy, who had more courage, Came to him and set himself on his knees, And greeted Godard courteously. Godard said, “What’s the matter with you? Why are you all bawling and yowling?" “Because we are bitterly hungry,” he said. “We need more to eat. We have no heat, nor do we have Either a knight or a servant in here Who gives us half the amount of food Or drink that we could eat. Woe is us that we were born! Alas! Is there not even grain That someone could make bread from? We are hungry and we are nearly dead!" Godard heard their plea, And did not care a straw about it, But lifted up both of the girls together, Who were green and pale from hunger, As if it were a game, As if he were playing with them. He slashed both of their throats in two, And then cut them to pieces. There was sorrow in whoever saw it When the children lay by the wall, Sprawled in the blood. Havelock saw it and stood there. The innocent boy was full of grief. He must have been frozen in terror, For he saw a knife pointed at his heart To rob him of his life. But the boy, who was so small, Kneeled before that Judas, And said, “Lord, have mercy now! Lord, I offer you homage. I will give you all of Denmark, On the promise that you let me live. I will swear on the Bible right here That I will never bear against you Shield or spear, Lord, Nor any other weapon that might harm you. Lord, have mercy on me! Today I will flee from Denmark And never come back again. I will swear that Birkabeyn Never fathered me.” When the devil Godard heard that, He felt a slight twinge of guilt. He drew back the knife, which was warm From the innocent children’s blood. It was a miracle, fair and bright, That he did not slay the boy, But out of pity he held back. He felt strong regret for Havelock, And though he wished that he were dead, Godard not could bring himself To kill him with his own hand, the foul fiend! Godard thought as he stood by him, Staring out as if he were crazy, “If I let him go alive, He might cause me great trouble. I will never have peace, For he may bide his time to kill me. And if his life were taken away, And my children were to thrive, After my time they might be Lords of all Denmark! God knows, he shall be killed. I will take no other course! I will have him thrown into the sea, And there I'll have him drowned, With a solid anchor about his neck, So that he can't float in the water.” From there he immediately sent for A fisherman that he believed Would do all his will, And he said to him at once, “Grim, you know you are my servant; Will you do all my will That I order you to? Tomorrow I will free you And give you property, and make you rich, Provided that you take this child And bring him with you tonight. When you see the moonlight, Go into the sea and throw him in it. I will take on myself all the sin.” Grim took the boy and tied him up tightly, While the bonds might last, Which were made of strong rope. Then Havelock was in great pain; He never knew before what torment was! May Jesus Christ, who makes the lame walk And the dumb speak, Wreak revenge on Godard for Havelock! When Grim had tied him up fast, And then bound him in an old cloth, He tightly shoved in his mouth A gag of filthy rags, So that he could not speak or snort out Wherever he might carry or lead him. When he had done that deed And obeyed the traitor’s orders, That he should take him out And soak him in the sea In a bag, big and black, Which was the agreement they made, He immediately threw him on his back And took him home to his hut. Grim entrusted him to his wife Leve, And said, “Watch this boy As if you were saving my life! I will drown him in the sea. Because of him we will be made free, And have plenty of gold and other goods; My lord has promised me this.” When Dame Leve heard this, She did not sit but jumped up, And dropped the boy down so hard That he banged his head Against a great rock laying there. Then Havelock might have been heard saying “Alas that I was ever a king’s son! If only he had fathered a vulture or eagle, A lion or wolf, a she-wolf or bear, Or some other beast to harm Godard back!" So the child lay there until midnight, When Grim asked Leve to bring a light In order to put on his clothes: “Don't you think anything of my oaths That I have sworn to my lord? I will not be ruined! I will take him to the sea— You know that’s what I have to do— And I will drown him there in the water. Get up quickly now and go in, And stoke the fire and light a candle!" But as she was about to handle his clothes To put them on him and kindle the fire, She saw inside a shining light, As bright as if it were day, Around the boy where he lay. From his mouth a gleam stood out As if it were a sunbeam. It was as light inside the hut As if candles were burning there. “Jesus Christ!” exclaimed Dame Leve, “What is that light in our hut? Get up, Grim, and see what it means! What do you think the light is?" They both hurried up to the boy, For people are naturally good-willed, Ungagged him, and quickly untied him, And then immediately found on him, As they pulled off the boy’s shirt, A royal birthmark on his right shoulder, A mark so bright and so fair. Grim said, “God knows, this is our heir Who will be lord of Denmark! He will be king, strong and mighty, And he will have in his hand All of Denmark and England! He will bring Godard great grief; He will have him hanged or flayed alive, Or he will have him buried alive. He will get no mercy from him.” Grim said this and cried bitterly, And then fell at Havelock’s feet And said, “My lord, have mercy On me and Leve, who is beside me! Lord, we are both yours— Your peasants, your servants. Lord, we will raise you well Until you know how to ride a steed, Until you know well how to bear A helmet on your head with shield and spear. Godard, that foul traitor, Will never know, for sure. I will never be a free man, Lord, Except through you. You, my lord, will release me, For I will protect and watch over you. Through you I will have freedom.” Then Havelock was a happy lad. He sat up and asked for bread, And said, “I am nearly dead, What with hunger, what with the ropes That you laid on my hands, And at last because of the gag That was stuck fast in my mouth. With all that I was so tightly pressed That I was nearly strangled!" Leve said, “God knows, I'm just pleased That you can eat. I will fetch you Bread and cheese, butter and milk, And meat pies and desserts. We'll soon feed you well with these things, My lord, in your great need. It’s true what people say and swear; 'No one can harm whom God wishes to help.'" When she had brought some food, At once Havelock began to eat Ravenously, and was very pleased; He could not hide his hunger. He ate a loaf, I know, and more, For he was half-starved. For three days before then, I guess, He had eaten nothing—that was clear to see! When he had eaten and was content, Grim made him a comfortable bed, Took his clothes off, and tucked him in, And said, “Sleep, son, in great peace. Sleep fast and do not be afraid of anything. You have been brought from sorrow to joy.” Soon it was the light of day. Grim made his way To the wicked traitor Godard, Who was the steward of Denmark, And said, “My lord, I have done What you ordered me to do with the boy. He is drowned in the water, With a firm anchor around his neck. He is surely dead. He will never eat any more bread! He lies drowned in the sea. Give me gold and other goods So that I may be rich, And make me free with your signature. You promised me these things in full When I last spoke with you.” Godard stood and looked at him Thoroughly with stern eyes And said, “So you want to be an earl? Get home quick, foul dirt-serf! Get out of here and be forever A slave and peasant as you were before! You will get no other reward. So help me God, it would take little For me to send you to the gallows. You have done a wicked thing. You stay here too long for your own good Unless you get out of here fast!" Grim thought, too late, as he ran From that traitor, that wicked man And pondered, “What will I do? If he knows he’s alive, both of us will be Hanged high on the gallows tree. It would be better for us to flee the land And save both of our lives, And my children’s and my wife’s.” Soon after Grim sold all of his grain, Sheep with wool, cattle with horns, Horses and pigs, goats with beards, The geese, and the hens of the yard. He sold all that could be sold, Everything that had value, And he converted it all to money. He outfitted his ship well enough. He gave it tar and a full coat of pitch So that it would never fear inlet or creek. He installed a fine mast in it, Fastened firmly with strong cables, Good oars, and a rugged sail. Nothing inside lacked even a nail That he should have put into it. When he had equipped it so, He put young Havelock in it, Himself and his wife, his three sons, And his two daughters, who were pretty girls. And then he laid in the oars And drew them out to the high sea Where he might best flee. He was only a mile from land, And it was no more than a short while When a breeze which men call The North Wind began to rise And drove them on to England, Which would later all be in one hand, And that man’s name would be Havelock. But before then he would endure Much shame, sorrow, and hardship. And yet he got it all completely, As you will all soon learn If you wish to hear about it. Grim came to land in the Humber, In Lindsay, right at the north end. There his fishing boat sat on the sand. But Grim drew it up onto the land, And built a little cottage there For him and his company. He began to live and work there, In a little house made of earth, So that in their harbor there They were well-sheltered. And because Grim owned that place, It took the name of Grim’s stead, So that everyone calls it Grimsby Who speaks about the town. And so men will always call it Between now and Judgment Day. Grim was a skillful fisherman And knew the waters well. He took plenty of good fish in, Both with a net and with a hook. He took sturgeons and whales, And turbot and salmon as well. He caught seals and eels, And was often very successful. He took cod and porpoise, Herring and mackerel, Flounder, plaice, and skate. He made fine bread baskets, One for him and another three For his sons to carry fish in To sell and collect money for upland. He missed neither town nor farm Wherever he went with his wares. He never came home empty-handed Without bringing bread and sauce In his shirt or in his hood, And beans and grain in his bag. He never wasted his efforts. And when he caught a great lamprey, He knew the road very well To Lincoln, the fine town. He often crossed it through and through, Until he sold everything as he wished And had counted his pennies for it. When he returned from there he was glad, For many times he brought home Cakes and horn-shaped breads, With his bags full of flour and grain, Ox-meat, lamb, and pork, And hemp to make fishing lines, And strong rope for his nets Where he set them in the sea. Thus Grim lived comfortably, And he fed himself and his household well For a good twelve winters or more. Havelock knew that Grim worked hard For his dinner while he lay at home. He thought, “I am no longer a boy. I am fully grown and can eat More than Grim could ever get. I eat more, by the living God, Than Grim and his five children. God knows, it can't go on like this. I will go with them To learn some useful skill, And I will labor for my dinner. It is no shame to work! It is a foul thing for a man who eats And drinks his fill who has not Worked hard for it to lie at home. God reward him more than I can For having fed me to this day! I will gladly carry the breadbaskets. I know it won't do me any harm, Even if they are a great burden, As heavy as an ox. I will no longer linger here. Tomorrow I will hustle forth!" In the morning when it was day He got up at once and did not lie down, And he threw a basket on his back With fish heaped up like a stack. He carried as much by himself As four men, by my word. He carried it firmly and sold it well, And he brought home every bit of silver, All that he got for it. He did not hold back a penny’s edge. He went out this way each day And was so eager to learn his trade That he never idled at home again. But it so happened that a bad harvest Brought a shortage of grain for bread, So that Grim could find no good solution To how he should feed his household. He was very anxious about Havelock, For he was strong and could eat More than every mouth there could get. Nor could Grim catch on the sea Either cod or skate, Nor any other fish that would serve To feed his family. He was very worried about Havelock And how he might fare. He did not think of his other children; All of his thoughts were on Havelock, And he said, “Havelock, dear son, I fear that we must all die from hunger, For this famine is so bad And our food is long gone. It would be better if you go on Than to stay here for long. You might leave here too late. You know very well the right way To Lincoln, the fine town, For you have been there often enough. As for me, my efforts aren't worth a bean. It’s better that you go there, For there are many good men in town And you might be able to earn your dinner there. But woe is me! You are so poorly dressed, I would rather take my sail and make Some clothing you can go in, son, So that you need not face the cold.” He took the scissors off the nail, And made him a cloak from the sail, And then put it on Havelock. He had neither hose nor shoes, Nor any other kind of clothing. He walked barefoot to Lincoln. When he arrived there, he was at a loss. He had no friend to go to. For two days he wandered there fasting, For no one would feed him for his work. The third day he heard a call, “Porters, porters, come here, all!" The poor who went on foot Sprang forth like sparks from coals. Havelock shoved aside nine or ten, Right into the muddy swamp, And started forward to the cook. There he took charge of the earl’s food Which he was given at the bridge. He left the other porters lying And delivered the food to the castle, Where he was given a penny cake. The next day again he eagerly kept A lookout for the earl’s cook, Until he saw him on the bridge Where many fish lay beside him. He had bought the earl’s provisions From Cornwall, and continually called, “Porters, porters, come quickly!" Havelock heard it and was glad That he heard 'porters' called. He made everyone fall down Who walked or stood in his way, A good sixteen strong lads. As he leaped up to the cook, He shoved them down the hillside, Hurrying to him with his basket, And began to scoop up the fish. He bore up a good cartload Of squid, salmon, and broad flatfish, Of great lampreys, and of eels. He did not spare heel or toe Until he came to the castle, Where men took his burden from him. When men had helped take down The load off his shoulders, The cook stood and smiled on him And decided he was a sturdy enough man And said, “Will you stay with me? I will be glad to keep you. The food you eat is well earned, As well as the wages you get!" Havelock said, “God knows, dear sir, I will ask you for no other pay But that you give me enough to eat. I will fetch you firewood and water, Raise the fire, and make it blaze. I can break and crack sticks, And kindle a fire expertly, And make it burn brightly. I know well how to split kindling And how to skin eels from their hides. I can wash dishes well, And do all that you ever want.” The cook said, “I can't ask for more! Go over there and sit, And I will bring you some good bread, And make you soup in the kettle. Sit down now and eat your fill. Damn whoever begrudges you food!" Havelock sat down at once, As still as a stone, Until he had fully eaten. Havelock had done well then! When he had eaten enough, He came to the well, drew up the water, And filled a large tub there. He asked no one to go with him, But he carried it in between his hands, All by himself, to the kitchen. He asked no one to fetch water for him, Nor to bring provisions from the bridge. He bore turf for fuel, and grass for kindling. He carried wood from the bridge; All that they might ever need, He hauled and he cut. He would never have any more rest Than if he were a beast. Of all men he was the most modest, Always laughing and friendly in speech. He was forever glad and pleasant; He could fully hide his sorrows. There was no boy so little Who wanted to sport or have fun That he would not play with him. For all the children who came his way, He did everything they wanted, And played with them to their fill. He was loved by all, meek and bold, Knights, children, young, and old. All took to him who saw him, Both high and low men. Word spread far and wide of him, How he was great, how he was strong, How handsome a man God had made him, Except that he was almost naked. For he had nothing to wear Except a rough cloak, Which was so dirty and foul That it was not worth a stick of firewood. The cook began to feel sorry for him And brought him brand new clothes. He bought him both hose and shoes, And soon made him put them on. When he was clothed, hosed, and in shoes There was no one so handsome under God Who was ever yet on earth, No one that any mother ever bore. There was never a man who ruled A kingdom who looked so much Like a king or emperor As he appeared when he was clothed. For when they were all together In Lincoln at the games, And the earl’s men were all there, Havelock was taller by a head Than the greatest who were there. In wrestling no man grappled him Whom he didn't soon throw down. Havelock stood over them like a mast. As high as he was, as long as he was, He was just as hardy and strong. In England he had no equal in strength Among whoever came near him. As much as he was strong, he was gentle. Though other men often mistreated him, He never insulted them Or laid a hand on them in malice. His body was pure of maidens; Never in fun or in lust would he Flirt or lie with a loose woman, No more than if she were an old witch. |

| 1000 1010 1020 1030 1040 1050 1060 1070 1080 1090 1100 1110 1120 1130 1140 1150 1160 1170 1180 1190 1200 1210 1220 1230 1240 1250 1260 1270 1280 1290 1300 1310 1320 1330 1340 1350 1360 1370 1380 1390 1400 1410 1420 1430 1440 1445 |

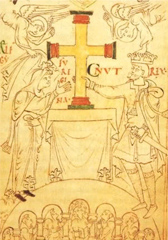

In that time al Hengelond Th’erl Godrich havede in his hond, And he gart komen into the tun Mani erl and mani barun, And alle that lives were In Englond thanne wer there, That they haveden after sent To ben ther at the parlement. With hem com mani chambioun, Mani with ladde, blac and brown, And fel it so that yungemen, Wel abouten nine or ten, Bigunnen the for to layke. Thider komen bothe stronge and wayke, Thider komen lesse and more That in the boru thanne weren thore - Chaunpiouns and starke laddes, Bondemen with here gaddes, Als he comen fro the plow. There was sembling inow; For it ne was non horse-knave, Tho thei sholden in honde have, That he ne kam thider, the leyk to se. Biforn here fet thanne lay a tre, And pulten with a mikel ston The starke laddes, ful god won. The ston was mikel and ek gret, And al so hevi so a neth; Grundstalwyrthe man he sholde be That mouthe liften it to his kne; Was ther neyther clerc ne prest, That mithe liften it to his brest. Therwit putten the chaumpiouns That thider comen with the barouns. Hwo so mithe putten thore Biforn another an inch or more, Wore he yung, wore he hold, He was for a kempe told. Al so the stoden and ofte stareden, The chaumpiouns and ek the ladden, And he maden mikel strout Abouten the altherbeste but, Havelok stod and lokede thertil, And of puttingge he was ful wil, For nevere yete ne saw he or Putten the stone or thanne thor. Hise mayster bad him gon therto - Als he couthe therwith do. Tho hise mayster it him bad, He was of him sore adrad. Therto he stirte sone anon, And kipte up that hevi ston That he sholde putten withe; He putte at the firste sithe, Over alle that ther wore Twelve fote and sumdel more. The chaumpiouns that put sowen; Shuldreden he ilc other and lowen. Wolden he nomore to putting gange, But seyde, “Thee dwellen her to longe!" This selkouth mithe nouth ben hyd: Ful sone it was ful loude kid Of Havelok, hw he warp the ston Over the laddes everilkon, Hw he was fayr, hw he was long, Hw he was with, hw he was strong; Thoruth England yede the speche, Hw he was strong and ek meke; In the castel, up in the halle, The knithes speken therof alle, So that Godrich it herde wel: The speken of Havelok, everi del - Hw he was strong man and hey, Hw he was strong, and ek fri, And thouthte Godrich, “Thoru this knave Shal ich Engelond al have, And mi sone after me; For so I wile that it be. The King Athelwald me dide swere Upon al the messe gere That I shude his douther yeve The hexte that mithe live, The beste, the fairest, the strangest ok - That gart he me sweren on the bok. Hwere mithe I finden ani so hey, So Havelok is, or so sley? Thou I southe hethen into Inde, So fayr, so strong, ne mithe I finde. Havelok is that ilke knave That shal Goldeboru have!" This thouthe with trechery, With traysoun, and wit felony; For he wende that Havelok wore Sum cherles sone and no more; Ne shulde he haven of Engellond Onlepi foru in his hond With hire that was therof eyr, That bothe was god and swithe fair. He wende that Havelok wer a thral, Therthoru he wende haven al In Engelond, that hire rith was. He was werse than Sathanas That Jhesu Crist in erthe stoc. Hanged worthe he on an hok! After Goldeboru sone he sende, That was bothe fayr and hende, And dide hire to Lincolne bringe. Belles dede he ageyn hire ringen, And joie he made hire swithe mikel; But netheless he was ful swikel. He saide that he sholde hire yeve The fayreste man that mithe live. She answerede and saide anon, By Crist and bi Seint Johan, That hire sholde noman wedde Ne noman bringen hire to bedde But he were king or kinges eyr, Were he nevere man so fayr. Godrich the erl was swithe wroth That she swor swilk an oth, And saide, “Whether thou wilt be Quen and levedi over me? Thou shalt haven a gadeling - Ne shalt thou haven non other king! Thee shal spusen mi cokes knave - Ne shalt thou non other louered have. Datheit that thee other yeve Everemore hwil I live! Tomorwe ye sholen ben weddeth, And maugre thin togidere beddeth. Goldeboru gret and yaf hire ille; She wolde ben ded bi hire wille. On the morwen hwan day was sprungen And day-belle at kirke rungen, After Havelok sente that Judas That werse was thanne Sathanas, And saide, “Maister, wilte wif?” “Nay,” quoth Havelok, “bi my lif! Hwat sholde ich with wif do? I ne may hire fede ne clothe ne sho. Wider sholde ich wimman bringe? I ne have none kines thinge - I ne have hws, I ne have cote, Ne I ne have stikke, I ne have sprote, I ne have neyther bred ne sowel, Ne cloth but of an hold whit covel. This clothes that ich onne have Aren the kokes and ich his knave!" Godrich stirt up and on him dong, With dintes swithe hard and strong, And seyde, “But thou hire take That I wole yeven thee to make, I shal hangen thee ful heye, Or I shal thristen uth thin heie.” Havelok was one and was odrat, And grauntede him al that he bad. Tho sende he after hire sone, The fayrest wymman under mone, And seyde til hire, fals and slike, That wicke thrall that foule swike: “But thu this man understonde, I shall flemen thee of londe; Or thou shal to the galwes renne, And ther thou shalt in a fir brenne.” Sho was adrad for he so thrette, And durste nouth the spusing lette; But they hire likede swithe ille, Sho thouthe it was Godes wille - God that makes to growen the korn, Formede hire wimman to be born. Hwan he havede don him, for drede, That he sholde hire spusen and fede, And that she sholde til him holde, Ther weren penies thicke tolde Mikel plenté, upon the bok - He ys hire yaf and she is tok. He weren spused fayre and well, The messe he dede, everi del That fel to spusing, an god clek - The erchebishop uth of Yerk, That kam to the parlement, Als God him havede thider sent. Hwan he weren togidere in Godes lawe, That the folc ful wel it sawe, He ne wisten what he mouthen, Ne he ne wisten what hem douthe, Ther to dwellen, or thenne to gonge. Ther ne wolden he dwellen longe, For he wisten and ful wel sawe That Godrich hem hatede - the devel him hawe! And if he dwelleden ther outh - That fel Havelok ful wel on thouth - Men sholde don his leman shame, Or elles bringen in wicke blame, That were him levere to ben ded. Forthi he token another red: That thei sholden thenne fle Til Grim and til hise sone thre - Ther wenden he altherbest to spede, Hem forto clothe and for to fede. The lond he token under fote - Ne wisten he non other bote - And helden ay the rith sti Til he komen to Grimesby. Thanne he komen there thanne was Grim ded - Of him ne haveden he no red. But hise children alle fyve, Alle weren yet on live, That ful fayre ayen hem neme Hwan he wisten that he keme, And maden joie swithe mikel - Ne weren he nevere ayen hem fikel. On knes ful fayre he hem setten And Havelok swithe fayre gretten, And seyden, “Welkome, louered dere! And welkome be thi fayre fere! Blessed be that ilke thrawe That thou hire toke in Godes lawe! Wel is hus we sen thee on live. Thou mithe us bothe selle and yeve; Thou mayt us bothe yeve and selle, With that thou wilt here dwelle. We haven, louerd, alle gode - Hors, and neth, and ship on flode, Gold and silver and michel auchte, That Grim ure fader us bitauchte. Gold and silver and other fe Bad he us bitaken thee. We haven sheep, we haven swin; Bileve her, louerd, and al be thin! Tho shalt ben louerd, thou shalt ben syre, And we sholen serven thee and hire; And hure sistres sholen do Al that evere biddes sho: He sholen hire clothes washen and wringen, And to hondes water bringen; He sholen bedden hire and thee, For levedi wile we that she be.” Hwan he this joie haveden maked, Sithen stikes broken and kraked, And the fir brouth on brenne; Ne was ther spared gos ne henne, Ne the hende ne the drake: Mete he deden plenté make; Ne wantede there no god mete, Wyn and ale deden he fete, And hem made glade and blithe; Wesseyl ledden he fele sithe. On the nith als Goldeboru lay, Sory and sorwful was she ay, For she wende she were biswike, That she were yeven unkyndelike. O nith saw she therinne a lith, A swithe fayr, a swithe bryth - Al so brith, all so shir So it were a blase of fir. She lokede noth and ek south, And saw it comen ut of his mouth That lay bi hire in the bed. No ferlike thou she were adred! Thouthe she, “What may this bimene? He beth heyman yet, als I wene: He beth heyman er he be ded!" On hise shuldre, of gold red She saw a swithe noble croiz; Of an angel she herde a voyz: "Goldeboru, lat thi sorwe be! For Havelok, that haveth spuset thee, He, kinges sone and kinges eyr, That bikenneth that croiz so fayr It bikenneth more - that he shal Denemark haven and Englond al. He shal ben king strong and stark, Of Engelond and Denemark - That shal thu wit thin eyne seen, And tho shalt quen and levedi ben!” Thanne she havede herd the stevene Of the angel uth of hevene, She was so fele sithes blithe That she ne mithe hire joie mythe, But Havelok sone anon she kiste, And he slep and nouth ne wiste Hwat that aungel havede seyd. Of his slep anon he brayd, And seide, “Lemman, slepes thou? A selkuth drem dremede me now - Herkne now what me haveth met. Me thouthe I was in Denemark set, But on on the moste hil That evere yete cam I til. It was so hey that I wel mouthe Al the werd se, als me thouthe. Als I sat upon that lowe I bigan Denemark for to awe, The borwes and the castles stronge; And mine armes weren so longe That I fadmede al at ones, Denemark with mine longe bones; And thanne I wolde mine armes drawe Til me and hom for to have, Al that evere in Denemark liveden On mine armes faste clyveden; And the stronge castles alle On knes bigunnen for to falle - The keyes fellen at mine fet. Another drem dremede me ek: That ich fley over the salte se Til Engeland, and al with me That evere was in Denemark lyves But bondemen and here wives; And that ich com til Engelond - Al closede it intil min hond, And, Goldeborw, I gaf thee. Deus! lemman, what may this be?" Sho answerede and seyde sone: “Jesu Crist, that made mone, Thine dremes turne to joye · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · That wite thu that sittes in trone! Ne non strong, king ne caysere So thou shalt be, fo thou shalt bere In Engelond corune yet. Denemark shal knele to thi fet; Alle the castles that aren therinne Shaltou, lemman, ful wel winne. I woth so wel so ich it sowe, To thee shole comen heye and lowe, And alle that in Denemark wone - Em and brother, fader and sone, Erl and baroun, dreng and thayn, Knightes and burgeys and sweyn - And mad king heyelike and wel. Denemark shal be thin evere ilc del - Have thou nouth theroffe douthe, Nouth the worth of one nouthe; Theroffe withinne the firste yer Shalt thou ben king of evere il del. But do now als I wile rathe: Nim in wit lithe to Denemark bathe, And do thou nouth on frest this fare - Lith and selthe felawes are. For shal ich nevere blithe be Til I with eyen Denemark se, For ich woth that al the lond Shalt thou haven in thin hond. Prey Grimes sones alle thre, That he wenden forth with the; I wot he wilen the nouth werne - With the wende shulen he yerne, For he loven thee hertelike. Thou maght til he aren quike, Hwore-so he o worde aren; There ship thou do hem swithe yaren, And loke that thou dwelle nouth - Dwelling haveth ofte scathe wrouth.” Hwan Havelok herde that she radde, Sone it was day, sone he him cladde, And sone to the kirke yede Or he dide any other dede, And bifor the Rode bigan falle, “Croiz” and “Crist” bi to kalle, And seyde, “Louerd, that all weldes - Wind and water, wodes and feldes - For the holy milce of you, Have merci of me, Louerd, now! And wreke me yet on mi fo That ich saw biforn min eyne slo Mine sistres with a knif, And sithen wolde me mi lyf Have reft, for in the se Bad he Grim have drenched me. He hath mi lond with mikel unrith, With michel wrong, with mikel plith, For I ne misdede him nevere nouth, And haved me to sorwe brouth. He haveth me do mi mete to thigge, And ofte in sorwe and pine ligge. Louerd, have merci of me, And late me wel passe the se - Though ihc have theroffe douthe and kare, Withuten stormes overfare, That I ne drenched therine Ne forfaren for no sinne, And bringe me wel to the lond That Godard haldes in his hond, That is mi rith, everi del - Jesu Crist, thou wost it wel!” Thanne he havede his bede seyd, His offrende on the auter leyd, His leve at Jhesu Crist he tok, And at his swete moder ok, And at the Croiz that he biforn lay; Sithen yede sore grotinde awey. Hwan he com hom, he wore yare, Grimes sones, for to fare Into the se, fishes to gete, That Havelok mithe wel of ete. But Avelok thoughte al another: First he kalde the heldeste brother, Roberd the Rede, bi his name, Wiliam Wenduth and Huwe Raven, Grimes sones alle thre - And seyde, “Lithes now alle to me; Louerdinges, ich wile you shewe A thing of me that ye wel knewe. Mi fader was king of Denshe lond - Denemark was al in his hond The day that he was quik and ded. But thanne havede he wicke red, That he me and Denemark al And mine sistres bitawte a thral; A develes lime he hus bitawhte, And al his lond and al hise authe, For I saw that fule fend Mine sistres slo with hise hend: First he shar a two here throtes, And sithen hem al to grotes, And sithen bad in the se Grim, youre fader, drenchen me. Deplike dede he him swere On bok that he sholde me bere Unto the se and drenchen ine, And wolde taken on him the sinne. But Grim was wis and swithe hende - Wolde he nouth his soule shende; Levere was him to be forsworen Than drenchen me and ben forlorn. But sone bigan he forto fle Fro Denemark for to berthen me. For yif ich havede ther ben funden, Havede he ben slayn or harde bunden, And heye ben hanged on a tre - Havede go for him gold ne fe. Forthi fro Denemark hider he fledde, And me ful fayre and ful wel fedde, So that unto this day Have ich ben fed and fostred ay. But now ich am up to that helde Cumen that ich may wepne welde, And I may grete dintes yeve, Shal I nevere hwil ich lyve Ben glad til that ich Denemark se! I preie you that ye wende with me, And ich may mak you riche men; Ilk of you shal have castles ten, And the lond that thor til longes - Borwes, tunes, wodes, and wonges. · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · |