Election Satire is Alive and Well; Maybe Too Well

By Ken Eckert

December 23, 2008

A fuller version of this essay was published as “The Evolution of Mean: Satire in the American Elections of 1980 and 2008 Compared” in Popular Culture Review 16 (2010).

Slate pundit Troy Patterson wrote back in April 2008 about “the Satire Recession,” arguing that the satire in the recent election was little more than “personality jokes” that rarely rise above cutesy, ad-hominem gags. The Canadian CBC also tut-tutted that American election satire was little more than “yo’ mama” routines about John McCain’s age. Post-election pundits claim guiltily that in a post-Bush era better times generally make for feebler political humor. Yet a closer comparison to other elections in the last thirty years reveals the opposite: that satire in 2008 is alive and well, and more biting, more partisan, and more aware of its own influence than before.

Consider as a good example the 1980 American presidential elections. The campaign featured a president with horrendous approval ratings who was seen as impotent in managing military problems in the middle east, and whose domestic policies ended in stagnation and energy crisis. Sound familiar? Jimmy Carter eventually squandered his gracious southern goodwill and was trounced by the genial, affable Ronald Reagan. The severest criticism of the Carter presidency came from cartoonists. As a visual medium, part of the joke was depicting Carter as a dwarf with giant lips, but the panels usually parodied Carter’s vacillation or ineffectiveness. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Jeff McNelly pictured Carter as a hapless Pollyanna holding a deed to the Brooklyn Bridge signed by Leonid Brezhnev, saying “You mean he lied to me?"

Yet this was as strong as things got. Most of the media parodied not the candidates’ issues or actions, but their personal tics, the “pseudo-satire” which Patterson now criticizes. Much of the spoofing merely riffed on the comedic stereotype which the candidate represented. Teddy Kennedy was introduced as “the senator from Pizza Hut.” Fat guy: check. Gerald Ford was a one-gag character on Saturday Night Live, where Chevy Chase would depict him tripping, dropping his papers, and falling in the pool. Klutz: check. Carter’s trademark gaffe would be the swamp rabbit which he claimed to be attacked by on a canoe ride. While it certainly suggested Carter’s leadership impotence, the joke grew into a Monty-Pythonesque gag of its own. Killer bunny: check.

Incisive satire exposes and shames reality. Much election humor in 1980, however, is what Russian theorist Mikhail Bakhtin would call in his work on Rabelais the carnival style of folk humor. A medieval festival day often involved parodies of authority figures; the church usually indulged the revelers and distinguished between something done “in ernest or in pley,” as Chaucer would say. Bakhtin argues folk humor includes the speaker as a target; “it is directed at all and everyone.” Comedians such as Bob Hope made fun of Reagan with friendly vaudeville gags, saying the only reason people voted for him is that they were afraid he would “go back to acting.” As Stephen Wagg says in his book, Because I Tell a Joke or Two: Comedy, Politics and Social Difference, such humor operates within the system and does so respectfully; it was “a bit of institutionalised cheek and the President laughed to confirm that this was OK.” The style is that of a celebrity roast, and one of Hope’s DVD compilations is tellingly titled “Laughing With the Presidents,” and not at.

The other quirk of old-school media is the expectation that both sides should be presented. Fair play is not a part of satire—George Orwell does not give the Soviets equal time in Animal Farm—but at the time network comedians such as Johnny Carson, and humorists such as Dave Barry, were expected to make fun of Carter and Reagan equally. The safest route in election humor has always been to tease each candidate but save the heavy fire for broader institutional targets: the campaign prattle; the glad-handing congressman; the form-obsessed bureaucrat. Even politicians themselves can join in, as Reagan did when he said that politics is the second oldest profession, but “it bears a very close resemblance to the first.” The motive of network executives might not have been so much fairness as economics. Television programs were broadcast to as general an audience as possible, and the genuine satirist might, at best, alienate half his audience, and at worst confuse them. Yet a satirical attack is toothless if it is obvious that the comedian is merely playing a role in jest. The humorist is kidding; Alexander Pope is not.

Sometime around 1984, to paraphrase Virginia Woolf, human character changed. The media universe exploded through satellite technology, as cable television stations dedicated to special audiences such as news and rock videos bloomed. Other developments were demographic, as more youth-oriented entertainers such as David Letterman eclipsed the older generation. By the mid-80s satirical treatments of “Ronnie Ray-Gun” had turned nasty. Reagan was a regular on the Spitting Image puppet show and mocked in pop songs such as Simply Red’s “Money’s Too Tight to Mention” (1985), which fades out with the sexual taunt, “Did the earth move for you, Nancy?” A graphically violent 1984 video for Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Two Tribes” features Reagan and Soviet leader Konstantin Chernenko in a bloody cage fight to decide their countries’ issues. This new bluntness anticipated things to come, and the media taunting of Vice President George Bush Sr. as an effeminate Reagan lackey —the “wimp factor"—likely contributed to the growing anti-intellectualism of the party in following elections.

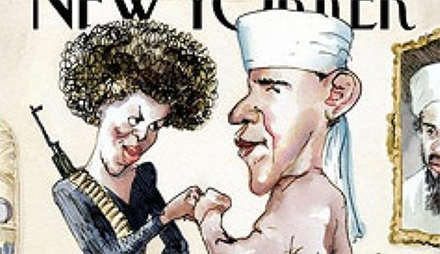

In some aspects the 2008 election was a replay of 1980, where an increasingly negative McCain campaign failed to dent Barack Obama’s affable optimism. The satirical tone of the election, however, was considerably different. Physical exaggeration is normally a staple of political cartooning, but making fun of Obama’s appearance evidently had unpleasant racial connotations—and so the text had to carry the joke, and it did with a new bite. The 60’s press would not have mocked JFK’s war experience, but McCain’s continually trotting out his POW ordeals eventually exasperated pundits; one Doonesbury panel has a journalist asking McCain to e-mail the press a document, and McCain replying, “You know, my friend, I didn’t have a fancy laptop in prison.” McCain’s age also led to morbid cartoons portraying running mate Sarah Palin after his death. This went beyond the typical stock jokes about Reagan and jelly beans or Bill’s libido. A good test for trenchant satire is how many people miss the joke, and the New Yorker cover of Obama dressed as a radical Muslim found an effective way to address an unsavory topic, even at the risk of having many people read the cover straight.

Yet the general influence of print has waned in favor of a much wider media universe than existed a generation earlier. The economic constraints of having to entertain a general audience are less applicable to much new television programming, and are irrelevant in the explosion of specialized and personal websites. There are fewer checks by advertisers or good taste on mocking political candidates. Northrop Frye, in “The Nature of Satire,” would call obscenity “an essential characteristic of the satirist,” and good satire is not above a fart joke; but much recent humor has been especially prurient, such as the pornographic film “Who’s Nailin’ Paylin” with a Palin lookalike. Independent videos supporting or attacking candidates were uploaded to sharing site YouTube, such as ’Obama Girl’. In one episode Obama Girl calls ’Hilary Clinton’ to convince her to support Obama, only to be told, “Thank you! I worked my whole life to be president only to be thwarted by a girl in hotpants… [well], this fifth of Jack Daniels isn’t going to drink itself.” Cracked’s online site has an edited concession speech where McCain says, “I call on all Americans, as I have often in this campaign… to wound… Senator Obama.”

This sort of viral internet humor is sharper and perhaps more satirical in a purer sense than Bob Hope (the words ’zany’ and ’antics’ are never good signs). Although some internet spoofing can have an element of carnival silliness, it is no longer with the candidates. The field is no longer dominated by Hollywood or Washington entertainers, and most internet humorists have not met the politicians they satirize. Their tone is not of a joshing intimate. Bakhtin’s carnival jester is present in the crowd, but the blogger is usually physically isolated, in front of a monitor. Professional outlets such as the Huffington Post are gaining credibility as establishment media; but any dissident crank can create blogs, flash cartoons, or YouTube videos of independent satire unbeholden to commercial interests who might water it down for a wider audience.

The tradition of satirical bipartisanship has also waned, assisted by the ending of the FCC’s 1949 Fairness Doctrine in 1987, which had mandated addressing both sides of issues. These developments have brought satire that is biting and uncensored, but have also fostered highly partisan audiences where group amplification polarizes opinion. Chat board websites and blogs have no expectation of objectivity, and can be expressly one-sided and abusive to outsiders. Even the Huffington Post openly identifies itself as liberal. Few are in doubt on Michael Moore’s politics when he asks dryly in Dude, Where’s My Country? why the Arabs think America favors Israel: “Maybe it was when that Palestinian child looked up in the air and saw an American Apache helicopter firing a missile into his baby sister’s bedroom just before she was blown into a hundred bits. Touchy, touchy! Some people get upset over the pickiest things!"

Having extreme platforms often now tends to enhance celebrity rather than estranging one’s audience as political entertainers such as Rush Limbaugh have attracted loyal fans who cheer on outrageous statements. Many political radio shows, with their skits and angry rants, are closer in style to Howard Stern than Larry King. A few commentators have asserted that critic Ann Coulter’s writings are satirical, but the claim that her extremeness makes the joke obvious fails; Coulter’s thesis that Democrats “fill the airwaves with treason” is not self-evidently sardonic in a media environment which ordinarily says such things. Critics such as Tim Rutten who suggest that political correctness has “drained humor’s salutary bite from our politics” because of the New Yorker cover miss the larger picture of how polarized much of the mass media has become in a climate where internet users can post anonymous jibes with few outside controls.

The influence of the culture wars has extended to network television, which is increasingly given partisan labels. The McCain campaign’s claim of media bias is hardly new; Adlai Stevenson griped that the press was as objective about Democrats as dogs are about cats. Yet in no earlier election has media bias been such an issue for satire. Networks were singled out as being ’in the tank’ for Democrats in the 2008 campaign; Jay Leno quipped that the election was “a huge celebration over at Barack Obama headquarters, otherwise known as MSNBC.” Much of the sniping was directed at Fox network with its perennial right-wing bias, such as when David Letterman joked that “At the end of the evening, the electoral vote count was 349 for Obama, 148 for McCain. Or, as Fox News says, too close to call.”

Satire has itself become a political issue. In the 1970s Saturday Night Live was considered edgy for even depicting a president, even if Chevy Chase’s Ford did little more than pratfalls. In 2008 more people might have seen Tina Fey’s impression of Sarah Palin than the candidate, and bloggers joked they were difficult to distinguish; Fey’s statement on foreign policy that “I can see Russia from my house” was only slightly more risible than Palin’s original claim. SNL seemed to agree with the Clinton camp’s charge that the media was favoring Obama in a debate skit where the CNN moderators offer Obama a pillow and a hot and bothered Soledad O’Brien fans herself after Obama’s vacuous closing remark that journalists “can take sides; yes we can.” This was not quick gags but satire so pointed it was widely accused of influencing the election.

And so the current state of political humor is not the decline of the “satirical industrial complex.” 21st century satire has proved itself so far to be more vigorous, biting, and partisan than at any time since perhaps Pope. Are we sure this is a good thing? In 1972, Senator Edmund Muskie wept after a mean-spirited editorial suggested his wife was an alcoholic, and bumper stickers followed saying, “Vote For Muskie Or He’ll Cry.” Muskie dropped out of the presidential nomination race. Gentle Walter Mondale recoiled from the vitriol raised against him. Just before the 2008 election, a Montreal radio comedy team telephoned Sarah Palin herself , impersonating French President Nicholas Sarkozy. In embarrassing Palin by having her ignorantly praise fictional Canadian Prime Minister Stef Carse, a Quebecois entertainer, a week after the actual national election, a certain line had been crossed. We need not worry about Palin’s thin skin, but how many good and capable people will avoid politics because of such personal gotcha attacks?

It is de rigeur for lefties to blame everything on Reagan. Certainly, his ideological petulance in ending the Fairness Doctrine did not help. But no one could have anticipated shock-talk radio, Stephen Colbert, and the user-generated internet sites which have created such strong niche markets for darker and more partisan satire. Future events may reemphasize the carnival style of humor, but for now the more elegant, bipartisan tradition of print satire is fading. Political cartoonists are retiring without heirs. Berke Breathed’s Opus comic ended in November 2008 as its creator explained that with “the cable and Web technology allowing All Snark All the Time,” he wants to protect the strip from becoming as coarse and polarized as the climate around him. Even Dave Barry, with his humorous musings about his dogs and high-school pictures, ends a column wistfully by asking, “Now that this election is over, whatever the hell happened, can we please grow up and stop being so nasty to each other? Please? OK, I didn’t think so.” Even Barry senses the present ascendancy of mean. ![]()